Deep Synth: Polyphony

by kbob

This is Part 5 of several. Start at the beginning.

Polyphony

I wanted Deep Synth to be polyphonic. So I started planning how to share voices among notes. My goals:

-

one note is replicated across six octaves, as in the mono synth.

-

as notes are added, some voices move to the new notes. Some voices should move up, and some should move down. (the wandering oscillator effect). The voices should stay distributed across the six octave range.

-

no notes let the voices drift back to the chaotic buzzing pattern.

Let me explain the wandering oscillator effect. Deep Synth should have no lowest note, so it assigns voices in a pseudo-Shepard tone way. No note should be strictly lower or higher than any other note; the oscillators should be moving both up and down on every transition. I went into more detail in the previous post.

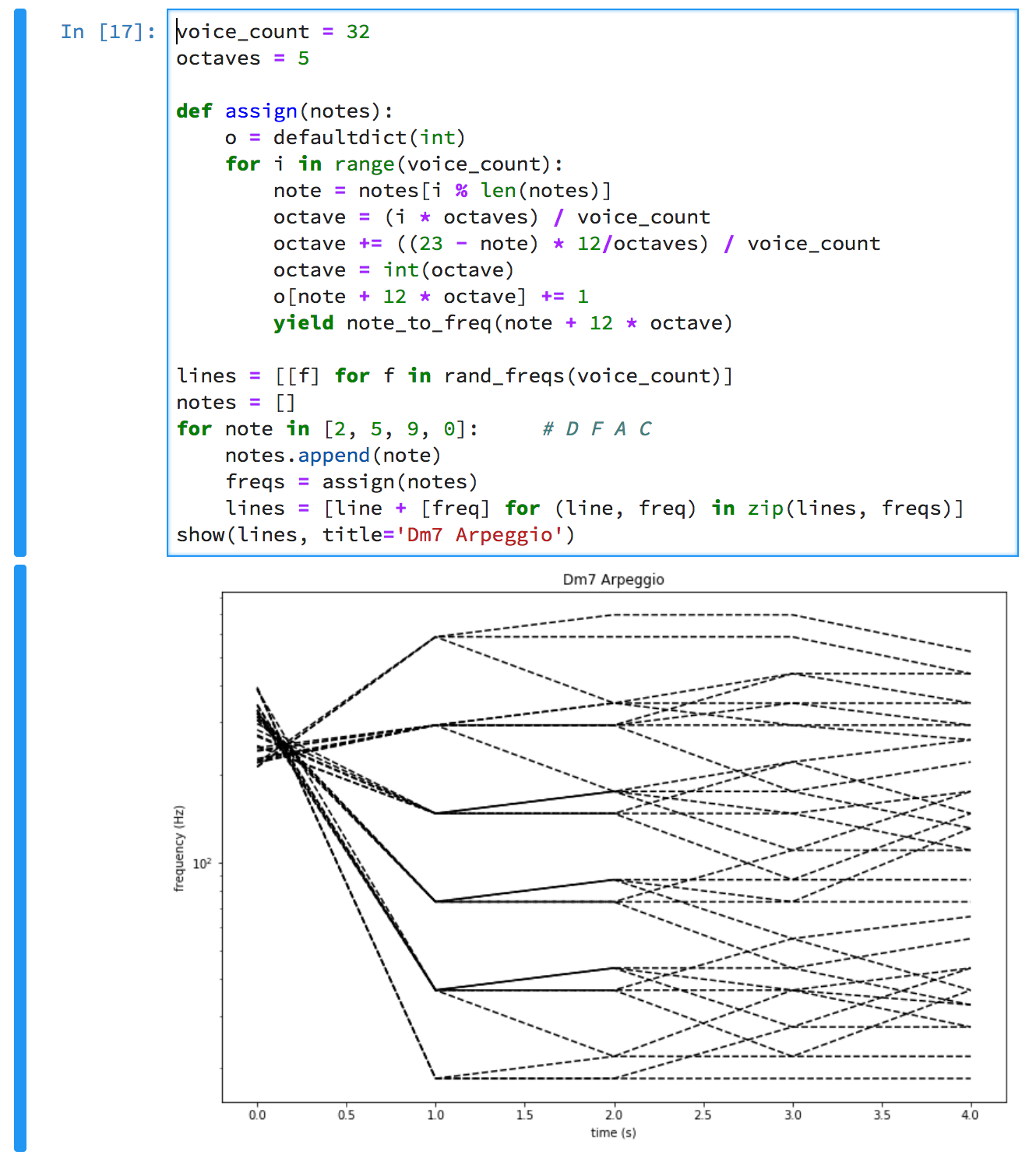

Again, I prototyped it in Jupyter notebook. Actually, you can see that I’m using exactly the same code to assign voices to notes. That’s because I’m fudging: I backported the new algorithm into the mono simulation to ensure it still works there. I don’t actually have a record of my Jupyter notebook before polyphony worked.

The graph shows the notes of a D minor 7th chord being added one at a time. At t=0, the voices are buzzing chaotically. At t=1, they are playing D in six octaves. Then F is added, and At t=2, half the voices have moved to F. At t=3, the voices have redistributed to D, F, A. And finally at t=4, we have the whole chord: D, F, A, C.

You can see that at each transition, voices are sliding both up and down.

There are 20 different notes in the final chord! It’s a deep chord [sic]. The magic of Shepard tones is that there is no definite bottom note. This chord is root and all three inversions, open and closed voicing, all at once.

Voice Transitions

But it still wasn’t right.

It’s easy to say, “voice should slide from this frequency to that”. But the way it slides is also important. After trying several things, I decided I wanted these properties:

-

When moving between notes, voices should ignore the chaotic buzzing frequency.

-

When notes are changing quickly, voices should move quickly.

-

When notes change before a voice has finished moving, it should start toward its new destination immediately and start moving faster.

-

Voice “blurring” (resuming chaotic buzzing) should start imperceptibly, then get faster.

-

Voices may start blurring before they’re fully focused on a note. And vice versa.

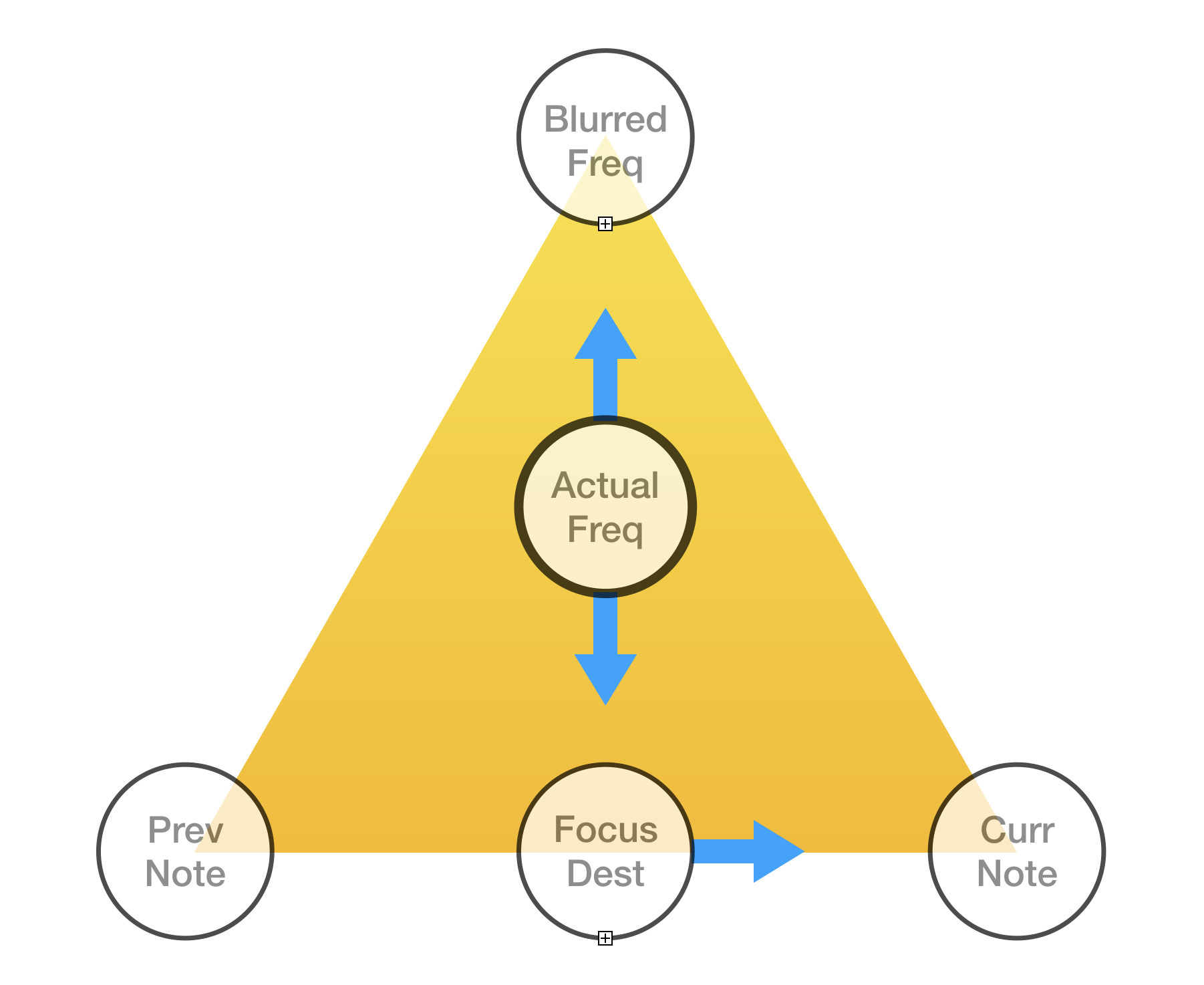

I eventually came up with this mental model.

The voice’s frequency is within the triangle. When the voice is focusing (moving toward a note because at least one note is triggered), the voice is moving toward the focus destination. Otherwise it is moving toward the blurred frequency. The focus destination is gradually moving from the previous note to the current note.

Here is the code to do that calculation. sweeper_interpolate

interpolates between 0 and 1 along an exponential curve; see below.

static float voice_freq(voice_state *vstate, voice_cfg const *vcfg)

{

float blur_freq = vcfg->rand_freq + vstate->rand_noise.level;

float prev_freq = vstate->prev_freq;

float dest_freq = vstate->dest_freq;

float focus_freq =

sweeper_interpolate(&vstate->slide, prev_freq, dest_freq);

focus_freq *= 1 + vstate->dest_noise.level;

return sweeper_interpolate(&vstate->focus, blur_freq, focus_freq);

}When the voice is assigned to a new note, Curr Note is set to the new note’s frequency. If the focused destination had reached the previous note, Prev Note is set to the previous note’s frequency. Otherwise, Prev Note is calculated so that Focus Dest does not have to change, either in its distance from Curr Note or its frequency.

That’s not a very good explanation. Here’s the relevant source.

float svalue = vstate->slide.value;

if (svalue == 1.0) {

// Previous slide finished. Start new slide.

vstate->prev_freq = vstate->dest_freq;

vstate->slide.value = 0.0;

sweeper_focus(&vstate->slide, &vcfg->slide);

} else if (svalue < 0.01) {

// Previous slide just started. Start new slide from

// current freq.

vstate->prev_freq = vstate->focus_freq;

vstate->slide.value = 0.0;

sweeper_focus(&vstate->slide, &vcfg->slide);

} else {

// Interrupted slide in progress. Slide faster from

// current freq to dest.

vstate->prev_freq =

(vstate->focus_freq + freq * (svalue - 1)) / svalue;

vstate->slide.value = 1.0 - svalue;

sweeper_focus(&vstate->slide, &vcfg->slide);

}

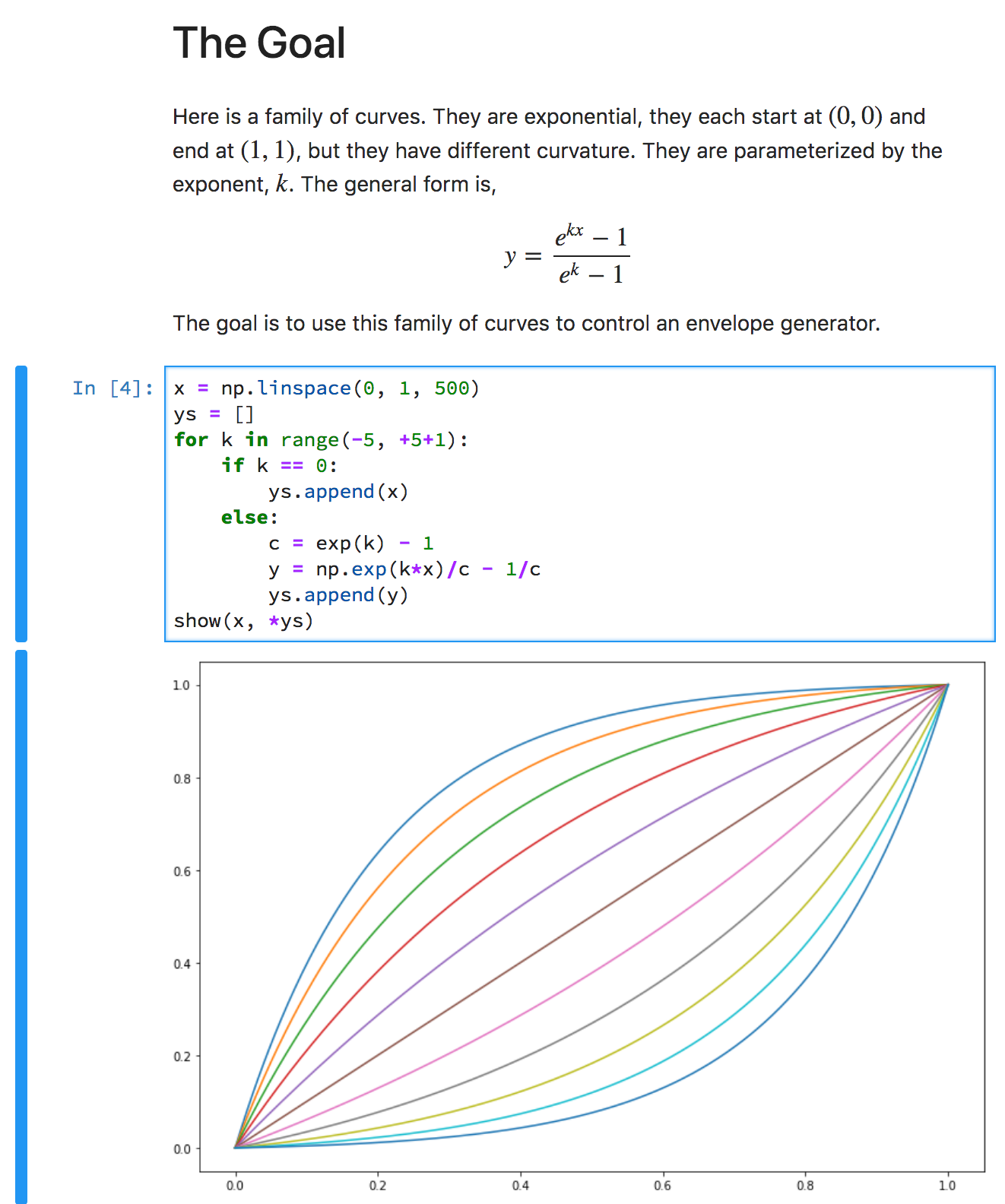

vstate->dest_freq = freq;Exponential Curves

I wrote a “class” called sweeper that interpolates along an

exponential curve. It’s designed to be fast to calculate and

easy to use.

I made another Jupyter notebook to understand exponential curves. (I love Jupyter notebooks. They are great if you think visually.) This one has explanatory text, so I’ll just paste it verbatim.

It’s a nice curve. You can start out slow and get faster, or start fast and slow down, and that’s independent of the total time or distance. You can scale x and y to the actual time and distance needed.

And it’s fast. Here is the code to increment position along the curve.

(sstate points to the sweeper’s mutable data.)

float value = sstate->value;

float delta = sstate->delta;

value += delta;

delta *= sstate->grow;

sstate->value = value;

sstate->delta = delta;You can find the complete implemention in

synth.c.

Look for things with sweeper in their names.

For each voice’s horizontal and vertical sweepers (slide and

focus), I used a random curve with 3≤k≤5. Those start slow

and end fast.